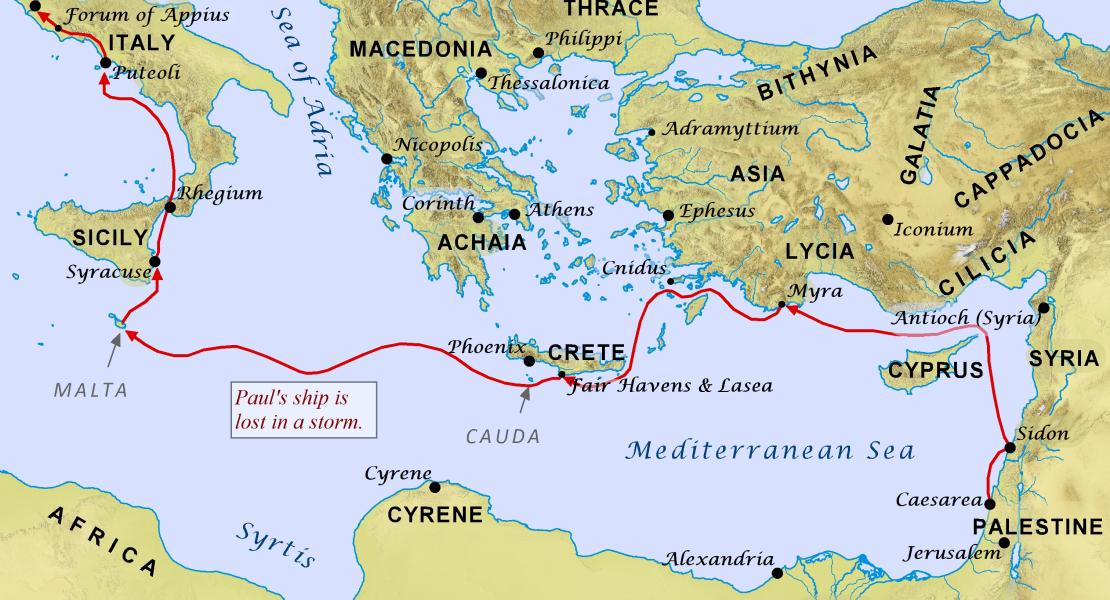

Following a few chapters focused in a couple local geographic areas, chapter 27 is a harrowing travel narrative of Paul and his companions being taken from Caesarea to Rome for his appearance before Caesar. This was no journey for the faint of heart, covering somewhere around 3000km of sailing! Today, 3000km isn’t at all a small distance—it’s roughly the direct distance between Penticton and Toronto—but we can cover it in about four hours in a plane. So the type of journey this is, well it’s rather hard for us to imagine.

(On a side note, these notes are being done on a day when winter storms are battering our area of the world. Interesting timing that this chapter would come up for us today...)

The map above shows the general outline of the travels, according to the names of places given in Acts 27. While there’s a ton of geographic detail early in the chapter, there is also a ton of theological detail especially later. As we work through this, there will be a few notes of background, though not as many as in previous chapters. Some of the notes will focus more on what we can learn from this narrative, and some of the cautions we need to take when considering how we learn from and apply the Bible accounts to our own lives. We can certainly do it, but we need to be discerning about how we do that.

27:1 Notice two things: 1. Luke shifts to “we” language again. He is again directly involved in the events and is now reporting as an eyewitness; and 2. the use of the passive voice “it was decided” (not “we” or “they” decided...); in many places in Scripture the passive voice strongly implies that YHWH is the agent of the action. This is an example where it’s more directly used in a human way. From a human perspective, it was decided not by Paul or Luke or one of their companions, but by the Roman officials.

And yet, we know from earlier (23:11), God told Paul he would be testifying in Rome. And so there is a sense (though we approach that carefully) in which this phrase may still be also a “divine passive”, as it clearly was the will of God that Paul would go to Rome. Whether to do the bulk of that journey over land or water wasn’t God’s explicit direction, but the destination certainly was.

27:2 Aristarchus had been with Paul on an earlier journey (20:4), and was there in prison with him too (Colossians 4:10, Philemon 24).

27:3 The Romain centurion allows Paul to go visit friends in Sidon; presumably these are fellow Christians there.

27:9 “The Fast” (ESV) is the Day of Atonement. That puts this part of the voyage in early October as we would know it, a time of year where things can start to get uncertain in terms of weather.

27:10-11 Paul offers some wisdom about the difficulty of travel, but is rejected. Not surprisingly, the opinion of those with business interests carry more influence. (Has anything really changed in our day?)

27:12 There is some kind of a council here; not just one person making the decision, but at least a small group. Using just those who’ve been mentioned, maybe it was the centurion, the pilot, and the owner. Perhaps there were others, but if not, then maybe it was the case that Paul was outvoted by these three.

27:13-20 For a short time, it seems like things were going fine with a gentle south wind. But then a “nor-easter” hit them hard and it looked like Paul’s wisdom was about to be fulfilled.

27:21-26 Paul then gently chides them for not listening earlier, but then reveals that God had revealed to him through an angel/messenger that no person would be lost on this voyage. Reflecting on this, it seems that for the sake of Paul, whom God had called to go to Rome, the whole ship’s personnel would be spared.

This is another Biblical example of a whole group of people being spared for the sake of one or a few. Of course, the best example of this is the whole of the Christian Church being spared because of Christ. What are other Biblical instances of this?

27:30-32 In fear of what might happen, some sailors take the “ship’s boat” (think of a sort of a lifeboat) that was towed behind but which was hauled up into the ship during the storm (27:16), and seek to escape. They didn’t trust Paul’s word that no one would be harmed, even though the ship would be lost.

Verse 31 is a most interesting verse. Here is an example (along with verses 24-25 that we mentioned above) of a passage that could easily be taken out of context as a simple “life lesson”. There are some who too easily “allegorize” Scripture; that is, they seek to extract some sort of moral lesson out of it and minimize the historical/factual nature of it. An allegory stands for something else, and so those who would allegorize Scripture tend to say that it doesn’t really matter if something actually happened in history or not, as long as we can learn something from it.

But Christianity is “grounded”. It’s grounded in real things, in real people, in real places, in real history. It does actually matter whether what’s recorded actually happened. Again, there are many examples of this, but the biggest one is the resurrection of Jesus; if that didn’t actually happen in history, then Christianity is worthless (see 1 Corinthians 15 for one reflection on this).

And so, in verse 31, Paul says, “unless these men stay in the ship, you cannot be saved”. It might be easy to allegorize that, where the ship simply represents commitment to something: “unless you stay committed to your course, you won’t finish it”. While that might be a good life lesson, it’s not good Bible teaching, not at all a good application of Acts 27:31. That’s not what God is teaching us here.

The primary point of the passage is historical; it’s simply describing what happened. God had revealed to Paul—for this specific voyage, not as a general life principle—that all people on the ship would be saved but the ship itself would be lost. For anyone to then seek to escape and put themselves ahead of others, that would mean the loss of life. But more specifically, if the sailors leave the ship, then the centurion, soldiers, and all other passengers who aren’t sailors would be put in mortal danger. If the crew abandons ship, what hope is there for the simple passengers? Paul shrewdly points this out to the Romans, and notice it’s the soldiers who cut the lines to the lifeboat, not the sailors.

Secondly, though, there is a wider application that we could discuss, though it must be approached carefully. We can only widen the application/learning of a given passage if Scripture itself give us the ability to do so.

In this case, we could say that it is generally true that one needs to remain “in the ship” of Christianity to be saved. Outside the Church there is no salvation. And if we wanted to “map” this a little more specifically, the “crew” could apply to church workers, most especially pastors; if pastors abandon Christ and the Scriptures, it can put the hearers in mortal danger.

And, the Scriptures do give us a way to support this, though it’s not directly an application of the specifics of this verse: in 1 Peter 3:20-22, Peter likens Noah’s ark to baptism, where people are saved through water. (And, in a follow-up to the question above re: verses 21-26, Noah’s ark is another example of a group of people being saved—eight in Noah’s family—on account of one: Noah.)

Throughout church history, the ark has been used as an image of salvation: inside the ark/ship/Church, there is salvation; outside it, loss. This is even why the part of a church building where the general seating is has been called a “nave”. That word comes from the Latin word navis, which means “ship” (think navy, naval, etc.). The Church is the “ship” of salvation.

Again, though, that’s not really the point of the verse. The account isn’t a parable, so application like this must be done carefully so as to not turn an account of an actual event in history into one, or into a sort of Aesop’s fable. But a verse like this can be what one theologian has called “a Gospel handle”, where the thing itself isn’t full of the Gospel (narrowly-defined, as in the Good News of salvation for sinners through Jesus), but it is something that can be “picked up and moved” into “Gospel territory”.

27:33-38 Here’s another example of where we need to be careful in applying the passage. It might be tempting to equate this with the Lord’s Supper because of the striking language of how Paul handled the bread. He “took bread, and giving thanks...he broke it and began to eat”. This is so very similar to the feeding of the many thousand by Jesus (which in itself isn’t the same as the Lord’s Supper, though there are familiar themes), and most especially of the description of what Jesus did on the night when he was betrayed. But just because the language used is similar doesn’t automatically equate things. The context is very different: this is not a church gathering and there are many unbelievers aboard.

So the most we can say with any confidence is that Paul was giving a witness to the source of this earthly strengthening: God. It’s clear that this episode is more earthly in nature. Paul knows they haven’t eaten in a long time, and this food will strengthen them. And yet, we can recognize the similarities for what they are: God has promised they would be saved, and they can be strengthened towards that by taking this food. And there is some sort of “table fellowship”—though not exactly the same as in the Lord’s Supper—which is a recurring theme of Luke-Acts as well.

27:39-44 The shipwreck finally occurs. True to their training, the soldiers want to prevent the prisoners’ escapes (remember, a soldier would receive the punishment due the prisoner, if that prisoner escaped). But the centurion—again notice for the sake of one (v. 43)!—prevents this. So they figure out a way to get everyone off the wrecked ship and onto land. And thus, all are indeed saved, though the ship is lost.